Two hundred years ago this week, the British navy occupied the island of Korčula during the Adriatic campaign against Napoleon’s revolutionary France. The Royal Navy’s knowledge of the region probably went no further than the setting of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. Peter Lowen, the captain of one of the ships did discover similarities with Shakespeare’s quasi-mythical land of bright sunshine, excellent food and fine wine. Perhaps he was inspired by Shakespeare to make the real Illyria look like the imagined one by helping to establish better government in what would become his home for over two years. Alongside Vis, Korčula became the second major British naval fortification in this part of the Eastern Adriatic. Although the British did not stay long enough to introduce the locals to cricket, croquet and cucumber sandwiches, they did leave subtle stone structures to symbolise their short settlement.

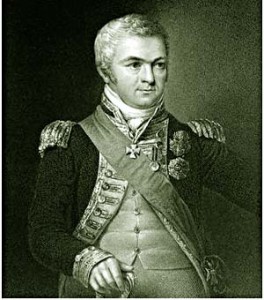

The Mediterranean had been a focus of attention since Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign and seizure of Malta. The defeat of Austria at the battle of Wagram in 1809 had put most of the Adriatic under French control. In the same year, Lord William Bentinck, the supreme commander of the Royal navy in the Mediterranean, decided to make the island of Vis the navy’s major Adriatic base. He despatched Admiral Thomas Fremantle to seize that Gibraltar of the Adriatic . From their strategic base, the British navy could support its royalist allies the Austrians and the Russians, prevent the French from acquiring ship-building capacity and disrupt Napoleon’s continental blockade. This often included attacking ships carrying supplies like grain and wine all along the Adriatic. Paradoxically, the blockade actions of the free-trade supporting British had a detrimental effect on the regional economy, causing severe supply shortages.

After the fall of Venice, Korčula and the Eastern Adriatic changed rule several times, being controlled by most of the major European powers. Austrian rule would be followed by brief Russian and French occupations. The Eastern Adriatic under French rule brought with its numerous progressive reforms such as civil rights, land reform and the first ever publication of a Croatian newspaper, the Kraglski Dalmatin. All this had been initially welcomed by sectors of the urban elite.

Whatever the benefits of French rule, significant conservative sectors of society such as the aristocracy, the peasantry and the clergy remained nostalgic for the status quo ante. The drain on the economy through high taxation, conscription as well as the effects of the multiple blockade meant that French rule became increasingly resented. By 1812, the French army had been demoralised after the retreat of the Grand Armée from Moscow. Perhaps it was due to this that the French contingent surrendered without much resistance on the 3 February 1813 to Fremantle. Two British ships, the Apollo and Imogene, dropped anchor near the Island of Vrnik, off the coast of today’s Lumbarda and ended French rule of Korčula on 4 February 1813.

Having taken Korčula, Fremantle established an agreement with the inhabitants creating a British protectorate. Like in later overseas endeavours, not having a written constitution back home did not prevent the Royal Navy from writing one abroad. The local constitution, written in Italian, stressed freedom of religion and the reinstatement of the church’s position. The admiral was proud of his of efforts to introduce local self-government and states in his diaries that: ‘I hope all I have been doing at Curzola may be useful to our cause. The constitution I have formed seems to answer all the purposes and I am much pleased by the reception I always get from the inhabitants.’ His diaries reflect a disappointment with the drunken behaviour of his sailors and an interest in the local population who unlike his sailors could hold their drink and dance elegantly.

Fremantle took the hearts and minds mission seriously, organising entertainment evenings such as balls for the local notables. The balls and entertainment coincided with the last days of the Carnival season, meaning that the overturning of daily life at this point in the year was not seen as uncommon by the locals. The admiral alongside Captain Lowen record dining with local families like the Boschi, whose suave style made a favourable impression on the naval officers. Over a century later, the British diplomat, adventurer and officer Sir Fitzroy Maclean is said to have bought the very same house that had hosted the naval officers.

Fremantle left Peter Lowen in charge, whose short administration of the island left structures still visible today. Coming from an island himself, Lowen seems to have developed a genuine affection for the sleepy medieval island, which led to numerous public projects being organised, not always with the consent of authorities in London. The construction projects all reflect the seafaring nature of contemporary Britain. The navy helped reconstruct the Western port of the city which was to become the major harbour for the city. The road from Lumbarda to the town itself was reconstructed using skilled local craftsmen.

Away from the historic town, overlooking the archipelago on the hill of St Blaise, a stern, poky and charmless watchtower was built to keep an eye on the canal dividing the continent from the island. The fortified watchtower was designed by Captain Taylor of the Frigate Appolo and built with the assistance of British crews from other ships which made detours to Korčula. Formerly known as the ‘English tower’, Fortezza, is still standing and on a clear day offers a sublime panorama of the surroundings. Observing the historic town and the dozen and a half island archipelago must have given the British a good view of approaching French and Russian shipping as well as how the Mediterranean fades into the mountains.

In 1815, in the aftermath of the treaty of Vienna, the British navy left Korčula on July 19. The treaty of Vienna allowed them to maintain a strong naval presence in the Mediterranean in Corfu, Malta and Gibraltar. Fremantle had made a huge fortune from the surrender of some eight hundred ships of the French fleet. His services led to him being made a baron of the Austrian empire and eventually in 1818, he became the Commander in chief of the British fleet in the Mediterranean. Although the British did not stay here as long as they did in Malta, Corfu and Cyprus, the naval officer’s frigates were followed later by a motley crew of British researchers, architects, writers, historians and military officers. Many would return and nurtured a lifelong link with the island.

Imbued with the spirit of the grand tour, in 1881, the Victorian travel writer and architect T G Jackson would stare from the Western side of the Adriatic and observe ‘the mysterious side of the Adriatic’. His book ‘Dalmatia, the Quarnero and Istria’ had an important impact on the UK, where the architectural splendours of Korčula and the surrounding region were visually and verbally revealed to a British audience for the first time. According to David Laven, a historian at Nottingham University; ‘Jackson tried to do for Dalmatia what Ruskin did for Venice and his legacy is important for British understanding of the region.’ One of his descendants, the renowned organist Sir Nicholas Jackson still performs regular concerts all over Dalmatia and performed in Korčula’s St Mark’s cathedral within the last decade.

Almost a century after Fremantle, the writer, regional expert and founder of the London School of Slavonic studies Robert Seton-Watson found in Korčula his first links to the South-Slavs intelligentsia, having been shunned by the aloof citizens of Dubrovnik. His private correspondence displays affection for ‘my favourite backwater where some of my best Croat friends live’ and the island as ‘harbour of refuge away from the lion’s den of Zagreb and Budapest’. Seton-Watson would be one of the main organisers of the sculptor Ivan Meštrović’s successful exhibition in London’s Victoria and Albert museum. His genuine fondness for the region and its people would be invaluable during the last years of Austro-Hungarian rule. His relentless lobbying against the British government excessive concessions to Italy in Treaty of London in 1915 proved invaluable. The disingenuous and duplicitous Treaty went against the principle of nationality by surrendering most of the Eastern Adriatic, including Korčula to the Italians during the First World War. In a memorable protest, no doubt influenced by his established local links, Seton-Watson claimed that: ‘Germany has a better right to Belgium and Holland than Italy to Dalmatia’.

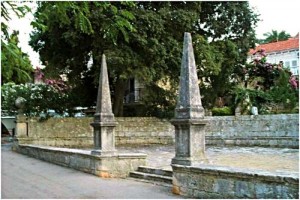

What would Lowen think of Korčula today, two hundred years after? In the summer, he would be familiar with the sight of English speaking lads unable to stomach let alone drink the local rakija. He would be glad to see that his stone structures were still in use. A short walk from the historic city, Lowen built a semi-circular stone terrace in classical style. The sizeable stone bench offers a charming vista over the Adriatic and the mainland. Perhaps regretting that he had never fought in the decisive battle of the Pyramids, Lowen flanked the entrance with two miniature obelisk which in a minimalist way resembles the pyramids. The paved resting place still retains the name as the ‘English piazza’. At the height of the tourist season a cocktail bar has been known to appear, though whether Peter prepared a primitive yet prime Pyms there has never been revealed.

Lowen seems to have caught the affection of the locals, who commemorated him with an inscription on the monument in Latin: ‘To Peter Lowen, during whose favourable administration this place of relaxation and this road suitable for wheels was built. Enjoying the freedom, the municipality of Korčula grants that this be commemorated.’ If Lowen was to have his tea there on a summer’s day, he would be delighted to see that since his last visit, the locals have adopted water polo, one of the British navy’s favourite sports, whose outdoor swimming pool is visible from the very piazza he built.